Communicative competence is a term used in linguistics to refer to language users’ knowledge of words and grammar, as well as their social knowledge about how and when to use utterances appropriately (Hymes, 1966; Canale and Swain, 1980). There are many facets of communicative competence, and many factors that influence the attainment of communicative competence.

In 1989, Janice Light identified and described four core domains necessary for individuals with significant speech and language disabilities who use AAC techniques, strategies and technologies to achieve communicative competence: operational, strategic, social, and linguistic. Psychosocial factors such as motivation, attitude, confidence, and resilience; as well as environmental barriers and supports (Light, 2003) can influence the development of communicative competence and are important to bear in mind during assessments and when planning interventions for individual children.

Operational Competence refers to learning the skills required to operate and use AAC devices, tools, and strategies. This includes learning to use signs and gestures, low-tech boards and speech generating devices (SGDs), mastering access methods (e.g., pointing, scanning, eye gaze, etc.), learning navigation patterns and locations of vocabulary, and caring for and maintaining devices and materials. People who rely on AAC need to learn how to operate mainstream technologies (phones, tablets, computers, wearable devices) as well. Different devices and strategies serve different purposes. Operational skill development should serve the student’s greater participation and overall communication goals, rather than achieving discreet skills in isolation. For example, a student’s ability to navigate through pages in their AAC device or their tablet device could actually detract from their overall participation and communication if navigating the device distracts from their interactions. Similarly, switch access should be thoughtfully targeted within real-life meaningful interactions or classroom routines.

Trevor and Miss Sasha practice his unique gesture for the video game ‘Wii’. Trevor thought that pointing to his arm reminded him of strapping the Wii remote around his arm. With a little bit of sharing and training, classroom staff quickly learned what this gesture meant.

Drew uses a multi-level encoded membrane keyboard to access a talking word processor to take her spelling test. She learned to use this keyboard and provided her input about the location of various keys over a number of teaching sessions with her Assistive Technologist, Speech-Language Pathologist, and Special Educator.

Jet learns to use an encoded letter board.

Strategic competence refers to learning strategies to overcome limitations and barriers encountered in the environment, experienced during interactions with other children and adults and/or inherent in an AAC system (e.g., insufficient vocabulary programmed into their device). Limitations and barriers may be temporary (e.g., experienced only when interacting with a partner who may not be familiar or comfortable with AAC) or longer-term. At The Bridge School, strategic competence involves learning when and how to use AAC tools and modes appropriately. Strategic competence requires that students learn how to use multiple communication modes effectively for different purposes across communication partners and contexts. These skills must be explicitly taught, which involves the SLP anticipating and recognizing the limitations of AAC systems, partners or the environment and then helping the student learn effective strategies for overcoming these limitations. Often communicative competence skills are taught by trained, highly responsive partners in a supportive environment and the communication barriers outside of that context may not be readily apparent to the student until they are experienced or explained.

Drew learns to use a speech-supplementation letter board on her tray that has letters facing her and letters facing her partner. Her communication partner sits face to face with her while talking. She touches the silver letters with her fist and her partner sees the white letters as she spells her message. This strategy of dual letter sets helps make her letter selections clearer for her partners because she obscures the letters with her fist as she makes her selections.

These ‘conversational control’ messages on a low-tech letter board help this student to prevent communication breakdowns, guide her partner through her various tools and modes (letter board, symbol book, gestures) and ensure her intended message is communicated effectively.

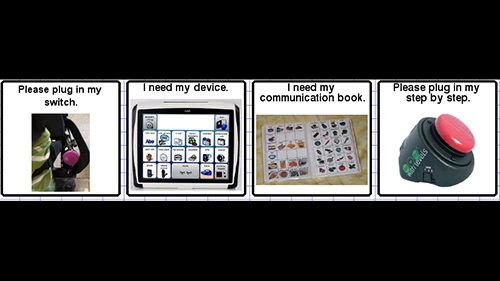

This small communication board is placed on the student’s wheelchair tray to help him direct partners to obtain his communication tools.

Social competence refers to learning how to use AAC tools and strategies to engage in effective social interactions. It includes learning discourse skills such as taking conversational turns, staying on-topic in a conversation and expressing many different communicative functions. Social competence focuses on the development of interpersonal skills that lead to, among other things, making friends and expressing a positive self-image and using appropriate social conventions across a variety of interactions and contexts (not just face-to-face conversations). Social competence skills should be appropriate to the student’s age, gender, and personal “style”, and also take into account the targeted partner, environment and reason for communicating. For example, when teaching a teenage student to use an appropriate greeting, the target skill or message might look very different for greeting a parent versus a teacher, close friend or a grandparent over the phone. Interventions that focus on teaching a student to use only one tool or device for all interactions do not address the various social demands of different interactions and contexts.

Drew practices using phrase-based messages on her SGD while playing a game during recess ‘games group’ with two peers from her 3rd grade classroom.

Linguistic Competence refers to knowledge, judgment, and skills in the individual’s native language within their family, school and community. This includes both spoken and written language. Additionally, students who rely on AAC must understand and use the representational strategies and/or codes that enable them to access language on various AAC systems and to participate in curricular activities.

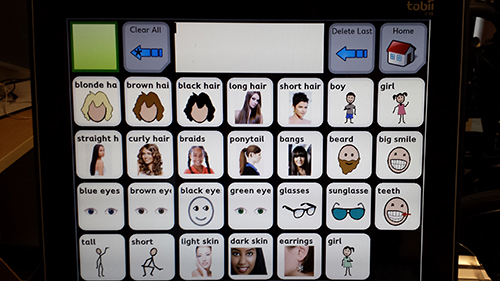

This student’s SGD contains descriptive vocabulary used during a language arts activity where students described themselves, their families, and story characters.

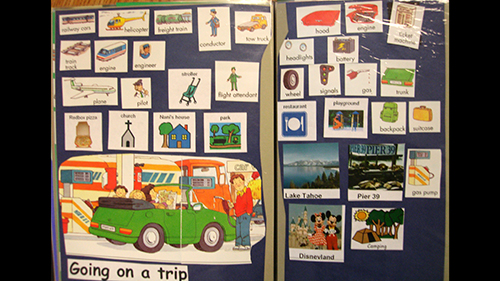

This preschool student’s low-tech symbol communication board contains general vocabulary concepts as well as personalized vocabulary for the ‘Transportation’ theme.